The Indispensable Role of Human Inspection in PCBA Manufacturing: Why Automation Hasn’t Replaced the Human Eye

Introduction

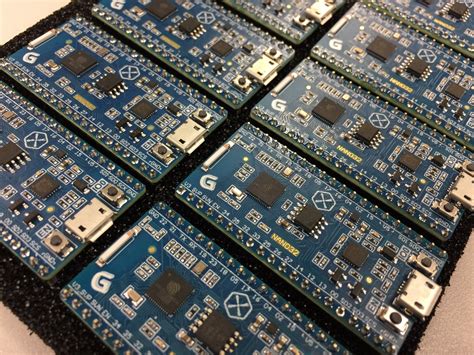

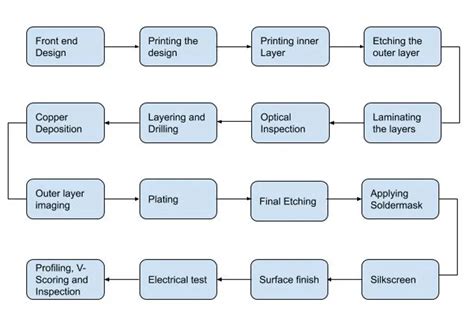

In an era where artificial intelligence and machine learning are transforming manufacturing processes, the Printed Circuit Board Assembly (PCBA) industry presents a fascinating paradox. While Surface Mount Technology (SMT) lines have achieved remarkable levels of automation—with pick-and-place machines operating at speeds of tens of thousands of components per hour and reflow ovens controlled to precise thermal profiles—human inspection remains an indispensable quality control checkpoint in virtually all PCBA manufacturing facilities. This paper explores the technical, practical, and economic reasons why human inspection continues to play a critical role in PCBA manufacturing, even as automated optical inspection (AOI) systems become more sophisticated and widespread.

The Limitations of Automated Inspection Systems

Resolution and Perspective Challenges

Modern AOI systems employ high-resolution cameras, sophisticated lighting systems, and advanced image processing algorithms to detect assembly defects. However, these systems still face fundamental limitations in their ability to replicate human visual perception. The human eye, when coupled with an experienced technician’s brain, can process visual information with remarkable flexibility—adjusting focus, perspective, and attention in ways that fixed camera systems cannot match.

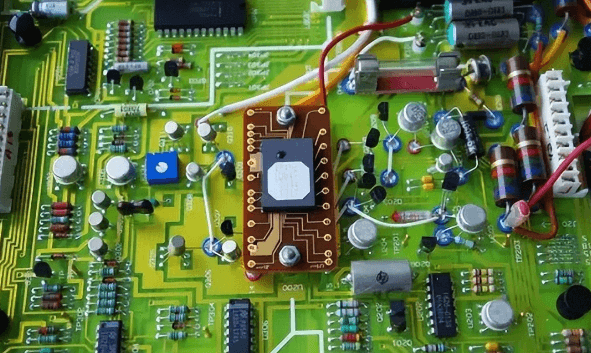

For through-hole components, particularly those with complex geometries or irregular shapes, human inspectors can manipulate the board to examine solder joints from multiple angles, something that even the most advanced 3D AOI systems struggle to do comprehensively. The ability to tilt a board to catch the telltale shine of a proper solder fillet or to spot subtle cracks in a joint remains uniquely human.

Contextual Understanding and Judgment

Human inspectors bring contextual understanding that goes beyond pattern recognition. While AOI systems excel at identifying deviations from predefined parameters, they lack the ability to make nuanced judgments about whether a particular anomaly actually constitutes a defect in a specific application context.

For example, a slight variation in solder paste deposition might be flagged as an error by an AOI system but would be recognized by an experienced human inspector as inconsequential for the particular component in question. Conversely, certain types of intermittent connections or subtle material defects might not trigger AOI alarms but would be caught by a vigilant human eye.

Programming and Threshold Limitations

AOI systems require precise programming of acceptable parameters, and these thresholds must be carefully balanced between being too strict (resulting in excessive false positives) and too lenient (allowing defective boards to pass). Human inspectors can dynamically adjust their scrutiny based on various factors—the criticality of the component, the product’s end-use environment, or even subtle visual cues that would be impractical to program into an automated system.

The Unique Capabilities of Human Inspectors

Multisensory Inspection

Human inspection engages multiple senses beyond just vision. Experienced PCBA inspectors often use tactile feedback (gently testing component seating) and even auditory cues (listening for the characteristic sound of a properly soldered joint when gently tapped) to assess quality. This multisensory approach provides a more comprehensive quality assessment than purely visual automated systems can achieve.

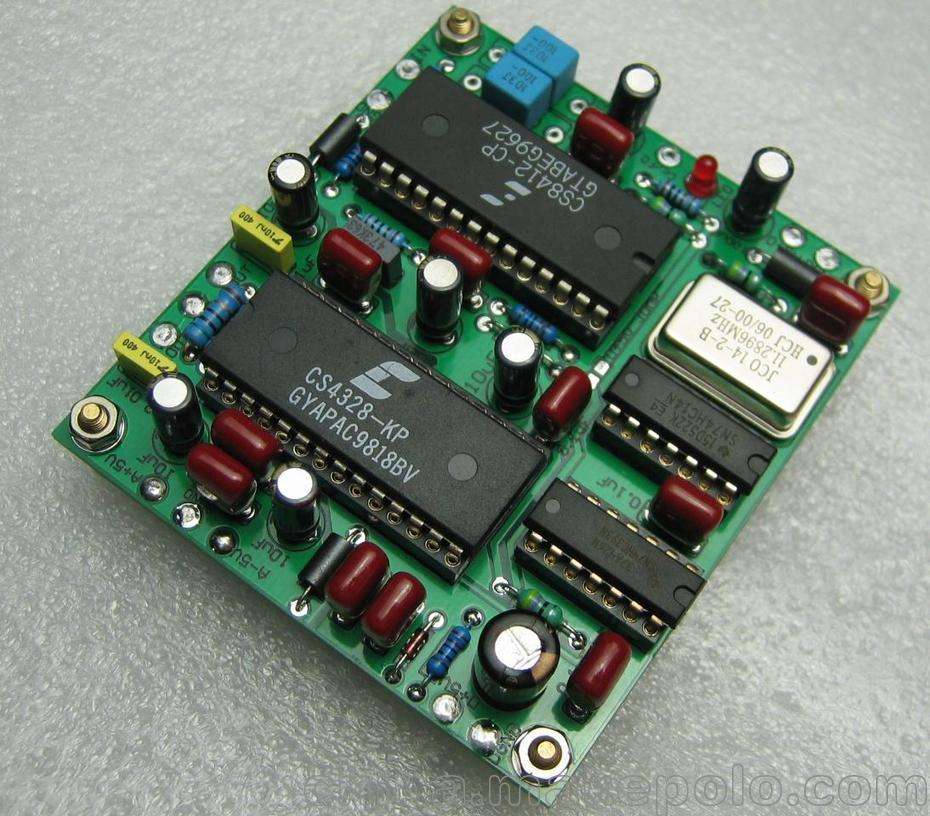

Adaptability to Design Changes

In low-volume, high-mix manufacturing environments—common in prototyping, aerospace, medical devices, and other specialized applications—the setup time required to program AOI systems for each new board design can be prohibitive. Human inspectors can quickly adapt to new designs without requiring reprogramming, making them more efficient for small production runs or rapidly evolving products.

Detection of Non-Visual Defects

Certain critical defects aren’t visually apparent but can be identified by human inspectors through functional tests or more nuanced evaluation. For instance, while an AOI system might verify that all components are present and properly aligned, a human inspector might notice that a particular IC seems unusually warm during power-up testing, suggesting potential issues not visible to cameras.

Economic and Practical Considerations

Cost-Effectiveness for Low and Medium Volume Production

For manufacturers producing small to medium quantities of PCBAs, the capital investment in high-end AOI equipment may be difficult to justify. A well-trained human inspection team can provide adequate quality control at a fraction of the cost, particularly when combined with selective use of automated inspection for critical areas.

Flexibility in Defect Analysis

When defects are identified, human inspectors can immediately begin root cause analysis, often recognizing patterns that would require complex programming in automated systems. This rapid feedback loop allows for quicker process adjustments and quality improvements on the production floor.

Handling of Non-Standard Components

Many PCBA designs incorporate non-standard components—mechanical parts, custom assemblies, or odd-form factors—that challenge the capabilities of even the most flexible AOI systems. Human inspectors can easily accommodate these variations without requiring special programming or fixturing.

The Synergy Between Human and Automated Inspection

Rather than viewing human and automated inspection as competing alternatives, leading PCBA manufacturers are finding optimal quality and efficiency by strategically combining both approaches. Common hybrid models include:

- AOI for High-Volume Defect Detection: Using automated systems to catch the majority of common defects (missing components, misalignments, obvious solder defects) at high speed.

- Human Inspection for Verification and Complex Defects: Having human inspectors review AOI-flagged items for false positives and perform more nuanced inspection on critical areas.

- Final Human Quality Assurance: Implementing a final human inspection checkpoint, particularly for high-reliability products, to catch any subtle issues that might have escaped automated detection.

Training and Maintaining Human Inspection Expertise

The continued importance of human inspection in PCBA manufacturing underscores the need for investment in inspector training and knowledge management. Key elements include:

- Structured Training Programs: Developing comprehensive training that covers both visual inspection techniques and understanding of electronic components and soldering standards.

- Reference Standards Maintenance: Keeping physical reference boards with known good and defective examples to calibrate inspector judgment.

- Continuous Skills Assessment: Implementing regular testing and calibration to ensure inspector consistency over time.

- Knowledge Transfer Systems: Capturing the tacit knowledge of experienced inspectors to benefit the entire quality team.

Future Outlook: Augmented Rather Than Replaced

Looking ahead, the role of human inspection in PCBA manufacturing is likely to evolve rather than disappear. Emerging technologies like augmented reality (AR) systems that overlay inspection guidelines directly onto the board, AI-assisted inspection stations that highlight potential areas of concern, and advanced imaging systems that enhance human capabilities all point toward a future where human inspectors are empowered with better tools rather than replaced by automation.

Particularly in high-reliability applications (medical, aerospace, automotive) and for complex, low-volume assemblies, the combination of human judgment with technological assistance will remain the gold standard for quality assurance.

Conclusion

While automated inspection systems continue to advance in capability and sophistication, human inspection remains an essential component of PCBA manufacturing quality control. The unique combination of flexible perception, contextual judgment, multisensory evaluation, and adaptive learning that human inspectors bring to the process cannot yet be fully replicated by machines. Rather than viewing human inspection as a legacy practice awaiting obsolescence, forward-thinking manufacturers recognize it as a complementary capability that—when properly trained, supported, and integrated with automated systems—provides the most comprehensive approach to PCBA quality assurance. As the electronics industry continues to demand ever-higher reliability while simultaneously driving toward greater product variety and faster time-to-market, the human eye and brain will remain indispensable tools in the PCBA manufacturing toolkit.