Key Considerations for Copper Pour in PCB Design

Introduction

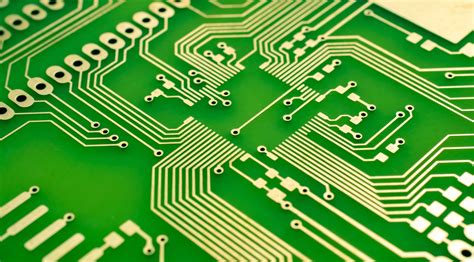

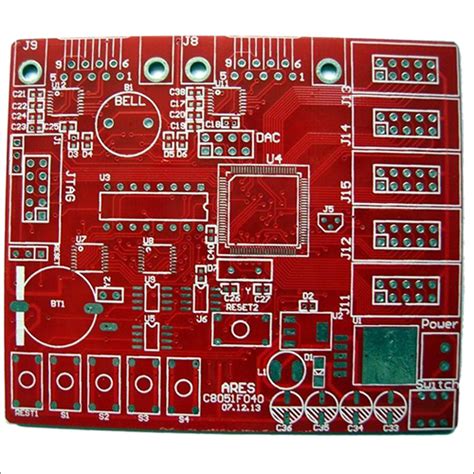

Printed Circuit Board (PCB) design involves multiple critical steps, and one of the most important among them is copper pouring (also known as copper fill or copper plating). Copper pouring refers to the process of filling unused areas of a PCB with solid copper, which is typically connected to a ground or power net. This technique enhances signal integrity, reduces electromagnetic interference (EMI), improves thermal dissipation, and minimizes manufacturing defects. However, improper copper pouring can lead to signal integrity issues, manufacturing challenges, and even circuit failures.

This article explores the key considerations for copper pouring in PCB design, including electrical performance, thermal management, manufacturing constraints, and best practices.

1. Electrical Considerations

1.1 Ground and Power Plane Connections

Copper pours are often connected to ground (GND) or power (VCC) nets to provide a low-impedance return path for signals. Key points to consider:

- Ground Copper Pour: Helps in EMI shielding and reduces noise by providing a stable reference plane.

- Power Copper Pour: Used to distribute power efficiently but must avoid creating unintended capacitive coupling.

- Floating Copper (No Net Connection): Should generally be avoided as it can act as an antenna, emitting or receiving interference.

1.2 Signal Integrity and Crosstalk

- High-Speed Signals: Ensure that copper pours do not create parasitic capacitance, which can degrade signal quality.

- Spacing Rules: Maintain sufficient clearance between copper pours and high-frequency traces to prevent crosstalk.

- Return Path Continuity: A solid ground plane beneath signal traces minimizes loop inductance and improves signal integrity.

1.3 Avoiding Ground Loops

- Stitching Vias: Use multiple vias to connect copper pours on different layers, reducing ground loop effects.

- Split Planes: If multiple ground domains exist (e.g., analog and digital grounds), ensure proper separation to prevent noise coupling.

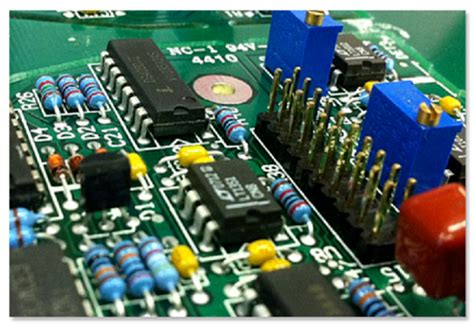

2. Thermal Management Considerations

2.1 Heat Dissipation

Copper pours help in spreading heat generated by components like power regulators, CPUs, and high-current traces.

- Thermal Relief Pads: Use thermal relief connections for component pads to prevent excessive heat sinking during soldering.

- Copper Thickness: Thicker copper (e.g., 2 oz or more) improves heat dissipation but may increase cost.

2.2 Avoiding Thermal Imbalance

- Uniform Copper Distribution: Uneven copper distribution can cause warping during reflow soldering.

- Copper Balancing: Ensure symmetrical copper distribution across layers to prevent PCB bending.

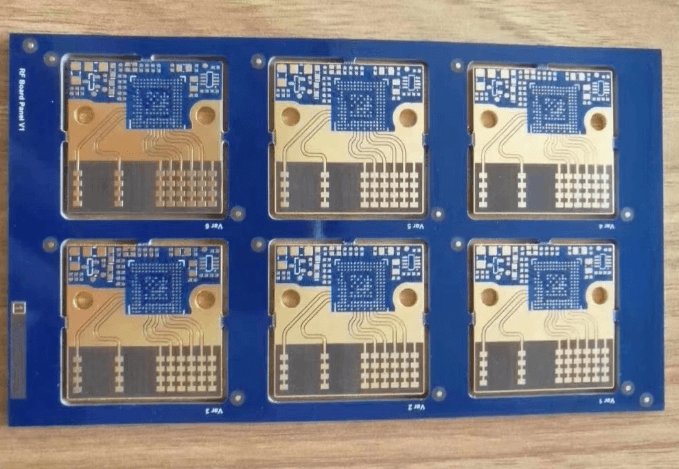

3. Manufacturing and Fabrication Considerations

3.1 Etching and Copper Thickness

- Minimum Copper Width: Ensure copper pours do not have extremely thin sections that may etch away.

- Copper Weight Selection: Standard PCBs use 1 oz/ft² copper, but high-power designs may require 2 oz or more.

3.2 Acid Trapping and Copper Thieving

- Acid Traps: Small gaps in copper can trap etching chemicals, leading to over-etching. Use smooth, rounded corners.

- Copper Thieving: Adding small, non-connected copper dots helps balance etching but should not interfere with signals.

3.3 Solder Mask and Silkscreen Clearance

- Solder Mask Openings: Ensure copper pours do not interfere with solder mask application, which can lead to solder bridging.

- Silkscreen Legibility: Avoid placing copper pours under text or component markings.

4. Best Practices for Copper Pour Implementation

4.1 Gridded vs. Solid Copper Pour

- Solid Copper Pour: Provides better EMI shielding and lower impedance but may cause warping.

- Gridded/Hatched Copper Pour: Reduces weight and thermal stress but may increase EMI radiation.

4.2 Clearance and Isolation Rules

- High-Voltage Isolation: Maintain sufficient clearance between high-voltage traces and copper pours to prevent arcing.

- Component Pads: Ensure copper pours do not create solderability issues (use thermal relief).

4.3 Layer Stackup Considerations

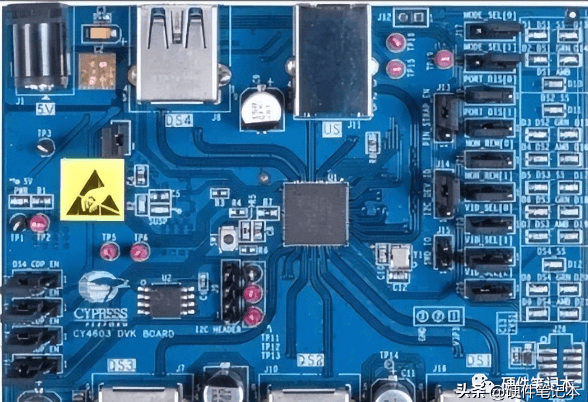

- Multilayer PCBs: Use copper pours on inner layers for better power distribution and shielding.

- High-Frequency Designs: Ensure uninterrupted ground planes beneath critical signal layers.

4.4 DRC (Design Rule Check) Validation

- Manufacturing DRC: Verify copper-to-trace, copper-to-hole, and copper-to-edge clearances.

- Electrical DRC: Check for unintended short circuits and floating copper sections.

5. Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

5.1 Excessive Copper in High-Frequency Areas

- Problem: Too much copper near RF traces can introduce parasitic capacitance.

- Solution: Use selective copper removal or adjust pour clearance rules.

5.2 Poor Thermal Relief Design

- Problem: Components with direct copper connections may suffer from cold solder joints.

- Solution: Always use thermal relief pads for through-hole and large SMD components.

5.3 Floating Copper Islands

- Problem: Unconnected copper can act as an antenna, causing EMI issues.

- Solution: Either connect them to a net (usually GND) or remove them entirely.

5.4 Inconsistent Copper Distribution

- Problem: Uneven copper can lead to PCB warping during assembly.

- Solution: Balance copper distribution across layers and use symmetrical designs.

Conclusion

Copper pouring is a powerful technique in PCB design that enhances electrical performance, thermal management, and manufacturability. However, it requires careful consideration of signal integrity, EMI, thermal effects, and fabrication constraints. By following best practices—such as proper grounding, thermal relief usage, and DRC validation—designers can avoid common pitfalls and optimize their PCBs for reliability and performance.

Whether designing high-speed digital circuits, RF systems, or power electronics, understanding these copper pour considerations will lead to more robust and efficient PCB layouts. Always simulate and verify designs before fabrication to ensure optimal results.