PCB Board Manufacturing vs. Prototyping: Key Differences Explained

Introduction

Printed Circuit Board (PCB) technology forms the foundation of modern electronics, with two fundamental processes serving different stages of product development: PCB manufacturing (board fabrication) and PCB prototyping (sample production). While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent distinct phases in the electronics production cycle with different objectives, processes, and requirements. This 2000-word article explores the 15 key differences between PCB board manufacturing and prototyping, providing electronics engineers, product designers, and procurement professionals with essential knowledge to make informed decisions throughout their product development journey.

1. Definition and Purpose

PCB Manufacturing (Board Fabrication):

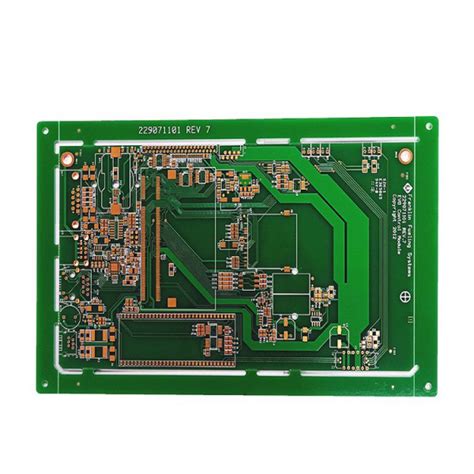

PCB manufacturing refers to the large-scale, volume production of printed circuit boards after the design has been fully validated. This is the mass production phase where hundreds, thousands, or even millions of identical boards are produced for commercial distribution or product assembly. The primary purpose is economic efficiency in producing reliable, standardized boards at the lowest possible per-unit cost.

PCB Prototyping (Sample Production):

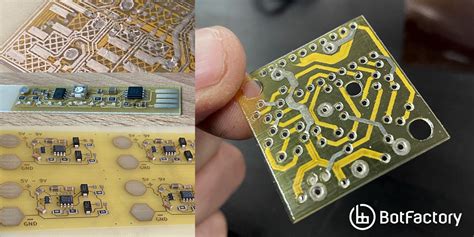

PCB prototyping involves creating small quantities (typically 1-50 units) of a board design for testing and validation purposes. Prototypes serve multiple functions: verifying circuit functionality, testing physical dimensions and component fit, evaluating thermal performance, and identifying potential manufacturing issues before committing to full-scale production. The emphasis is on speed and flexibility rather than cost efficiency.

2. Production Volume

The most apparent difference lies in quantity:

- Prototyping: Usually 1-50 pieces

- Small-batch production: 50-1,000 pieces

- Mass production: 1,000-1,000,000+ pieces

Prototyping quantities are sufficient for design verification but would be economically impractical for end-use products. Manufacturing quantities achieve economies of scale but require substantial upfront investment.

3. Turnaround Time

Time requirements differ significantly:

- Prototyping:

- Standard: 2-7 days

- Expedited: 24-48 hours

- Some services offer 8-hour “super rapid” prototyping

- Manufacturing:

- Standard: 10-20 days

- Expedited: 5-7 days (with premium pricing)

- Tooling setup alone may require 3-5 days

Prototyping services prioritize speed to accommodate iterative design processes, while manufacturing focuses on process optimization for quality and yield.

4. Cost Structure

The financial models differ substantially:

- Prototyping Costs:

- High per-unit cost ($5-$500 per board)

- Minimal or no tooling/NRE (Non-Recurring Engineering) charges

- Linear scaling with quantity

- Often includes additional engineering support

- Manufacturing Costs:

- Significant upfront tooling/NRE costs ($100-$10,000+)

- Dramatically lower per-unit cost ($0.10-$10)

- Non-linear cost scaling (economies of scale)

- Bulk material purchasing advantages

Prototyping is design-cost intensive, while manufacturing is tooling-cost intensive.

5. Materials Used

Material selection varies between phases:

- Prototyping:

- Often uses standard FR-4 with 1oz copper

- Limited material options to maintain quick turnaround

- May use higher-grade materials than necessary to ensure success

- Less focus on long-term material availability

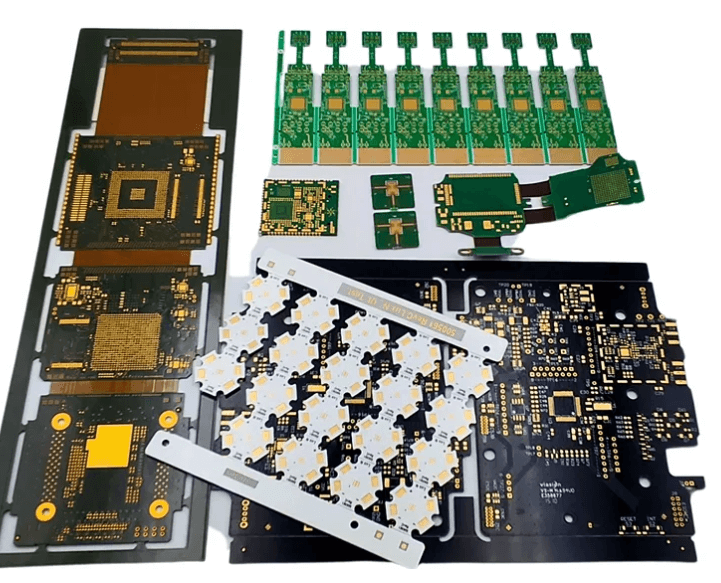

- Manufacturing:

- Optimized material selection for cost/performance

- May use specialized materials (high-frequency, flex, metal-core)

- Strict control of material supply chain

- Materials selected for long-term availability

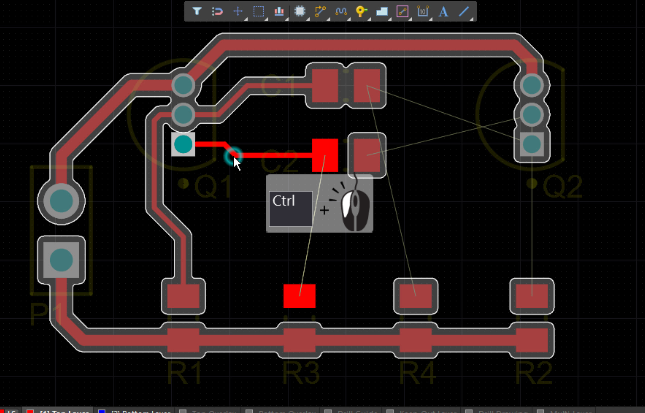

6. Design Flexibility

Design requirements differ:

- Prototyping:

- Accommodates last-minute design changes

- Tolerates non-optimized designs

- Can handle unconventional approaches

- Less strict about DFM (Design for Manufacturing) rules

- Manufacturing:

- Requires fully finalized designs

- Demands strict DFM compliance

- Limited flexibility once tooling is created

- Design changes extremely costly after production begins

7. Quality Standards

Quality expectations evolve:

- Prototyping:

- Focus on functional verification

- Some cosmetic imperfections tolerated

- Electrical testing may be sample-based

- IPC Class 1 or 2 typically acceptable

- Manufacturing:

- Strict cosmetic requirements

- 100% electrical testing common

- Statistical process control implemented

- Often requires IPC Class 2 or 3 certification

- Comprehensive quality documentation

8. Testing Procedures

Verification approaches differ:

- Prototyping:

- Basic continuity testing

- Functional verification

- May include bench testing

- Limited environmental stress testing

- Manufacturing:

- Automated Optical Inspection (AOI)

- In-Circuit Testing (ICT)

- Flying probe testing

- Burn-in testing for critical applications

- Batch-based reliability testing

9. Surface Finishes

Finish selection varies:

- Prototyping:

- Often uses HASL (Hot Air Solder Leveling)

- May offer ENIG (Electroless Nickel Immersion Gold) at premium

- Limited finish options

- Manufacturing:

- Multiple finish options (ENIG, Immersion Silver, OSP, etc.)

- Finish selected for specific applications

- Better process control for premium finishes

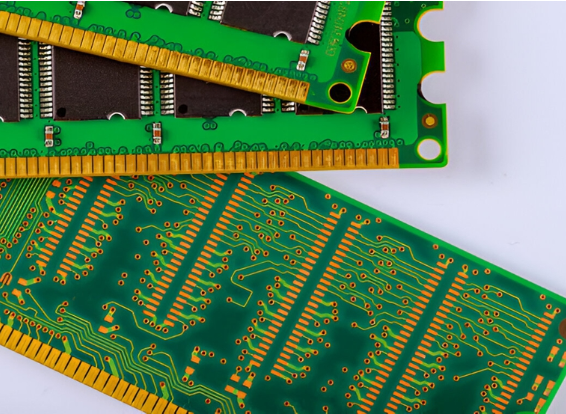

10. Layer Count Considerations

Stackup complexity differs:

- Prototyping:

- Typically 1-8 layers

- Some services offer up to 32 layers

- Less focus on layer stackup optimization

- Manufacturing:

- Commonly 2-16 layers

- Advanced production can achieve 50+ layers

- Precise impedance control

- Optimized layer stackups

11. Minimum Trace/Space

Feature sizes vary:

- Prototyping:

- Typically 5/5 mil trace/space

- Advanced services offer 3/3 mil

- Limited HDI (High Density Interconnect) capability

- Manufacturing:

- Can achieve 2/2 mil or better

- Microvias and buried vias common

- Advanced HDI processes available

12. Documentation Requirements

Paperwork expectations grow:

- Prototyping:

- Basic Gerber files sufficient

- May accept less formal documentation

- Limited compliance documentation

- Manufacturing:

- Complete Gerber, drill, and assembly files

- Detailed fabrication drawings

- Material certifications

- Compliance documentation (RoHS, REACH, etc.)

13. Supplier Relationships

Partnership dynamics differ:

- Prototyping:

- Transactional relationships

- Multiple vendors commonly used

- Less supplier qualification

- Price sensitivity lower

- Manufacturing:

- Strategic partnerships

- Extensive supplier qualification

- Long-term contracts common

- Significant price negotiation

14. Failure Analysis

Problem-solving approaches:

- Prototyping:

- Debugging expected

- Iterative problem-solving

- Engineering analysis focused

- Manufacturing:

- Root cause analysis

- Process capability studies

- Statistical methods (Six Sigma, etc.)

- Corrective action systems

15. Ordering Process

Procurement differs:

- Prototyping:

- Online instant quoting common

- Credit card payments accepted

- Minimal MOQ (Minimum Order Quantity)

- Self-service model

- Manufacturing:

- Custom quoting required

- Wire transfer/LC payments

- Significant MOQs

- Dedicated account management

Conclusion

Understanding the distinctions between PCB prototyping and manufacturing is essential for effective electronics development. Prototyping serves the needs of design verification, allowing for rapid iteration and flexibility, while manufacturing focuses on cost-efficient, reliable volume production. Smart product development utilizes both phases appropriately—using prototyping to de-risk designs and manufacturing to achieve business-scale economics. By recognizing these 15 key differences, engineering teams can better plan their product development cycles, allocate budgets effectively, and transition smoothly from concept to mass production.

The most successful electronics companies develop clear strategies for both prototyping and manufacturing, recognizing that each serves distinct but complementary purposes in the product lifecycle. Whether you’re a startup engineer creating your first prototype or a seasoned procurement professional managing global supply chains, appreciating these differences will lead to better technical and business outcomes.