Microtek PCB Design: Reverse Engineering & Analysis

Key Takeaways

When reverse-engineering Microtek PCB designs from the 1980s, you’ll encounter unique challenges rooted in obsolete component architectures and analog signal pathways. Understanding these systems requires a blend of forensic circuit analysis and historical context, especially when comparing them to modern PCB manufacturing practices. Unlike today’s standardized processes handled by large-scale PCB manufacturing companies, vintage Microtek boards often relied on custom fabrication methods, which directly influenced their PCB manufacturing cost and design longevity.

A critical step involves mapping trace routing patterns to infer logic flows, a task complicated by degraded solder joints or undocumented modifications. Tools like signal tracers and multilayer board scanners become indispensable here, bridging the gap between analog-era craftsmanship and digital-age precision. You’ll notice that PCB manufacturing business strategies from the 1980s prioritized durability over miniaturization, resulting in thicker substrates and through-hole components that contrast sharply with today’s surface-mount-dominated designs.

Preserving functionality demands reconciling legacy voltage requirements with contemporary power supplies—a process that often reveals how thermal stress and material aging have altered circuit behavior. For instance, carbon-film resistors in these systems may drift beyond tolerance thresholds, requiring careful substitution without compromising historical accuracy.

This work underscores the evolution of engineering priorities: where modern PCB manufacturing emphasizes cost-efficiency and scalability, Microtek’s designs reflect an era of bespoke problem-solving for specialized embedded applications. By studying these artifacts, you gain insights not just into component-level functionality, but also into the economic and technical constraints that shaped early PCB manufacturing companies.

As you progress, keep in mind that each board tells a story—of hand-soldered connections, manual testing protocols, and the gradual shift toward automated production. These layers of context transform technical analysis into a preservation effort, ensuring that the ingenuity behind 1980s Microtek PCB systems isn’t lost to obsolescence.

Reverse Engineering Techniques for Microtek PCB Circuitry

When reverse-engineering Microtek PCB designs from the 1980s, you begin by mapping the physical board layout using high-resolution imaging tools. This step reveals critical insights into layer stack-ups, trace routing patterns, and component placement strategies that defined early embedded systems. For boards with degraded labeling, specialized software like OpenCV or KiCad helps reconstruct schematics by analyzing solder joints and copper pathways.

A key challenge lies in reconciling outdated PCB manufacturing practices with modern analysis methods. Unlike today’s standardized processes, 1980s PCB manufacturing companies often used manual drilling and single-sided boards, complicating signal path tracing. To decode these systems, cross-referencing datasheets for legacy ICs—such as Zilog Z80 or Motorola 68000 processors—becomes essential.

Tip: Always document voltage test points before disassembling fragile boards. Use non-conductive probes to avoid damaging oxidized traces.

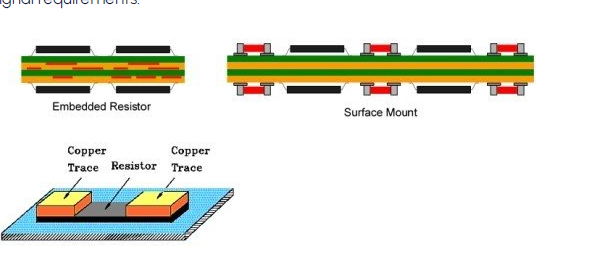

Understanding PCB manufacturing cost drivers of the era explains design compromises. For instance, Microtek frequently opted for through-hole components over pricier surface-mount technology (SMT), prioritizing reliability in industrial environments. When replicating these boards, collaborating with firms like Andwin PCBA ensures compatibility with vintage materials while adhering to modern safety standards.

Your toolkit should include:

- Signal analyzers to map clock frequencies

- Logic analyzers for bus traffic capture

- X-ray imaging for multilayer inspection

This process becomes particularly valuable when reviving discontinued PCB manufacturing business models. By comparing Microtek’s hand-routed layouts to contemporary automated designs, you uncover evolutionary shifts in noise reduction and power distribution strategies—lessons still relevant for hybrid analog-digital systems today.

Remember: reverse engineering isn’t just about replication. It’s a forensic study of engineering trade-offs made under 1980s technological constraints, offering actionable insights for preserving legacy hardware’s functionality.

Analyzing 1980s Microtek Embedded System Architecture

When reverse-engineering Microtek PCB designs from the 1980s, you’ll encounter a distinct architectural philosophy shaped by the technological constraints and engineering priorities of the era. Unlike modern pcb manufacturing workflows that prioritize miniaturization and high-speed signaling, these vintage systems relied on hand-routed traces and through-hole components, reflecting the industrial practices of early pcb manufacturing companies.

A typical Microtek embedded system of this period features a hierarchical layout divided into three functional blocks:

- Central processing unit (CPU) cluster: Often built around 8-bit microcontrollers like the Intel 8051 or Zilog Z80

- Analog signal conditioning circuits: Designed with discrete op-amps and passive filters

- Custom I/O interfaces: Tailored for industrial control applications

| Design Aspect | 1980s Microtek Approach | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Layer Count | 2-4 layers | 6-12+ layers |

| Trace Width | 15-20 mil | 3-5 mil |

| Component Density | 8-12/cm² | 50-100/cm² |

| Power Delivery | Linear regulators | Switching regulators |

The pcb manufacturing cost considerations of the time explain several architectural choices. Thick copper layers (2-3 oz) were standard to withstand repeated rework, while the absence of surface-mount technology necessitated larger board footprints. You’ll notice asymmetric power plane layouts—a cost-saving measure that contrasts sharply with today’s symmetric stackups in high-volume pcb manufacturing business operations.

Decoding these systems requires understanding their clock tree distribution methodology. Unlike modern designs with phase-locked loops (PLLs), Microtek engineers used daisy-chained clock buffers and RC networks for timing synchronization, creating unique signal integrity challenges when probing aged boards.

Critical preservation challenges stem from obsolete components—custom ASICs and EPROMs whose functionality modern pcb manufacturing companies no longer support. This forces engineers to create emulation profiles using programmable logic devices, bridging the gap between vintage architectures and contemporary repair workflows.

The transition to the next section on component-level analysis flows naturally from this architectural examination, as these system-level observations directly inform how you approach individual circuit blocks during reverse engineering.

Component-Level Breakdown of Vintage Microtek PCB Designs

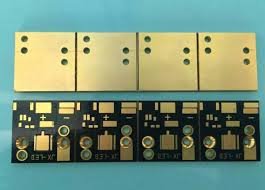

When examining vintage Microtek PCBs from the 1980s, you’ll notice their designs prioritize durability over miniaturization—a stark contrast to modern PCB manufacturing practices. These boards relied heavily on through-hole components, with PCB manufacturing companies of the era favoring discrete resistors, ceramic capacitors, and axial-lead diodes arranged in grid-like layouts. The visible traces, often hand-routed, reveal how engineers balanced PCB manufacturing cost constraints with the need for robust signal integrity in industrial embedded systems.

A closer look at power regulation sections shows bulky linear voltage regulators paired with electrolytic capacitors—components chosen for their reliability in harsh environments. This design philosophy reflects the priorities of the PCB manufacturing business at the time, where repairability and longevity outweighed compactness. Decoding these layouts requires understanding period-specific practices, such as using jumper wires to resolve routing conflicts instead of multi-layer boards.

Transitioning between functional blocks, you’ll find ceramic oscillator modules clocking Z80 or 6502 processors, their frequencies stabilized by hand-soldered crystal arrays. Analog sections, like audio or sensor interfaces, often feature op-amps with external compensation networks—a practice modern designers might replace with integrated solutions. The use of socketed ICs and dip switches underscores an era when field upgrades were common, aligning with the modularity goals of 1980s PCB manufacturing.

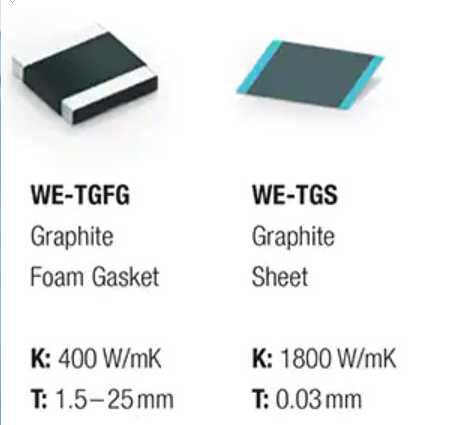

Analyzing these boards also highlights how thermal management was achieved passively: wide copper pours, strategically placed vents, and oversized ground planes. While inefficient by today’s standards, these methods reduced reliance on active cooling in systems where dust and vibration ruled out fans. This component-level granularity not only preserves historical engineering insights but also offers lessons for maintaining legacy hardware still in operation.

Tools and Methods for Decoding Legacy Microtek Hardware

When approaching reverse engineering of vintage Microtek PCBs, specialized tools bridge the gap between analog-era designs and modern analysis workflows. You’ll need a combination of hardware diagnostic equipment—such as high-resolution oscilloscopes and logic analyzers—paired with software tools capable of parsing legacy board layouts. For example, converting physical traces into digital schematics often requires PCB manufacturing-grade imaging systems, like X-ray tomography, to non-destructively map multilayer boards.

One critical method involves cross-referencing component libraries from the 1980s, as original datasheets for ICs like the MC6800 or Zilog Z80 may no longer be publicly archived. This demands collaboration with PCB manufacturing companies that retain historical archives or niche communities dedicated to retro hardware preservation. Advanced signal tracing techniques, such as parametric curve tracing, help identify degraded components by comparing their electrical behavior against known specifications.

Cost considerations also play a role: PCB manufacturing cost for recreating obsolete boards often exceeds modern equivalents due to custom fabrication requirements. For instance, replicating a single-layer phenolic substrate with through-hole components might involve outsourcing to specialty PCB manufacturing business partners, as standard FR-4 materials and surface-mount processes won’t match the original design intent.

Beyond physical tools, software emulators like SPICE or MAME (for embedded firmware analysis) enable functional testing without risking damage to fragile hardware. However, challenges persist in translating analog signal paths into digital models, particularly for proprietary interfaces unique to Microtek’s architecture.

Understanding these elements ensures your reverse-engineering efforts preserve both the functional integrity and historical accuracy of these systems, while highlighting how far PCB manufacturing practices have evolved since the 1980s.

Challenges in Preserving 1980s Microtek Circuit Functionality

When working with vintage Microtek PCBs, you’ll quickly realize that preserving their original functionality involves navigating a maze of technical and logistical hurdles. Unlike modern PCB manufacturing processes, which rely on standardized materials and automated workflows, 1980s-era boards were often built using proprietary fabrication techniques and materials that are no longer commercially available. For instance, the phenolic resin substrates common in early Microtek designs have largely been replaced by FR-4 fiberglass in contemporary PCB manufacturing companies, complicating efforts to replicate or repair aging boards.

One critical challenge lies in sourcing obsolete components. Many integrated circuits (ICs) and discrete parts used in these systems have been out of production for decades, forcing engineers to either salvage components from donor boards or redesign circuits using modern equivalents—a process that risks altering the original circuit functionality. Compounding this issue is the lack of comprehensive documentation. Original schematics, if they exist at all, may omit critical details like trace impedance values or component tolerance thresholds, which were often considered “trade secrets” at the time.

Another layer of complexity arises from the PCB manufacturing cost dynamics of the era. To minimize expenses, Microtek frequently employed manual soldering and through-hole designs, which differ starkly from today’s surface-mount technology (SMT)-driven workflows. Modern PCB manufacturing business practices prioritize high-density layouts and automated assembly, making it difficult to replicate the physical characteristics of vintage boards without costly custom tooling.

Perhaps most daunting is the risk of damaging irreplaceable hardware during analysis. Aged solder joints become brittle, and traces may delaminate when subjected to modern testing equipment. This forces a delicate balance between invasive probing and non-destructive imaging techniques like X-ray tomography—methods that were not part of 1980s engineering toolkits.

Ultimately, preserving these systems demands not just technical skill but also a deep understanding of how historical PCB manufacturing constraints shaped their design. Each decision—whether to replicate, emulate, or adapt—carries implications for maintaining the authenticity and operational integrity of these embedded time capsules.

Microtek vs Modern PCB Design: Evolution of Engineering Practices

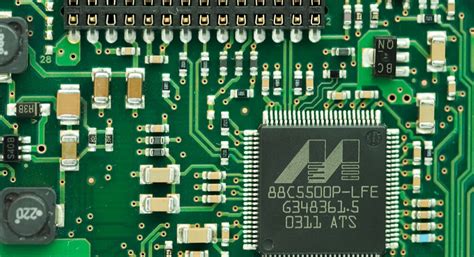

When examining PCB manufacturing practices across decades, the contrast between 1980s Microtek designs and modern methodologies reveals fundamental shifts in engineering priorities. Where vintage Microtek boards relied on manual layout techniques and bulky through-hole components, today’s PCB manufacturing companies leverage automated design software and high-density interconnects (HDI) to achieve compact, multilayer architectures. This evolution isn’t merely about miniaturization—it reflects changing demands for scalability, signal integrity, and thermal management in embedded systems.

In the 1980s, Microtek’s PCB manufacturing cost was driven by labor-intensive processes, including hand-drawn schematics and physical prototyping. Engineers prioritized durability over complexity, often using standardized dual in-line packages (DIPs) and straightforward trace routing. Fast-forward to modern workflows, and you’ll find simulation tools predicting electromagnetic interference (EMI) risks before fabrication begins, while design-for-manufacturability (DFM) principles optimize yield rates. The shift from analog-dominated circuits to mixed-signal designs also underscores how PCB manufacturing business models now emphasize flexibility for rapid iteration.

Material science further highlights this divergence. Microtek’s fiberglass-based substrates, while robust, lacked the thermal stability of today’s high-Tg laminates or flexible polyimide films. Modern boards integrate advanced coatings to resist humidity and corrosion—critical for applications like IoT devices or automotive systems. Yet, retrofitting vintage Microtek designs poses challenges: their single-layer layouts and discrete logic chips resist direct translation to contemporary surface-mount technology (SMT), requiring creative adaptations during reverse engineering.

The economic landscape has shifted too. Where Microtek’s era favored localized PCB manufacturing, globalized supply chains now enable cross-border collaboration, reducing turnaround times but introducing complexities like component obsolescence. This progression invites reflection: while modern tools streamline production, the tactile problem-solving of 1980s engineering still offers lessons in resilience and simplicity.

Case Studies in Microtek Embedded System Reverse Engineering

When reverse-engineering vintage Microtek embedded systems, you’ll encounter unique challenges that reveal how PCB manufacturing practices have evolved since the 1980s. Take, for example, a case study involving a factory automation controller from 1985. By deconstructing its multi-layer board, engineers identified hand-routed traces and through-hole components—a stark contrast to modern automated PCB manufacturing companies that rely on surface-mount technology. This discovery highlights why understanding historical design philosophies is critical: legacy layouts often prioritize durability over miniaturization, a principle that shaped PCB manufacturing cost calculations of the era.

Another case examines a telecommunications interface board, where reverse engineers used X-ray imaging to map buried vias. Here, the absence of standardized design files forced teams to cross-reference schematics with physical components, a process complicated by obsolete ICs. Such scenarios underscore the value of collaborating with specialized PCB manufacturing business partners who retain archives of legacy materials. You’ll notice that these boards often feature redundant power rails and oversized traces—design choices that reflect the limited simulation tools available to engineers at the time.

In one industrial control module, analysts discovered hybrid analog-digital circuits that blended op-amps with early microcontroller units. Decoding these required oscilloscopes and logic analyzers to reconstruct signal pathways—a method far removed from today’s software-driven verification processes. These case studies demonstrate how reverse engineering not only preserves functionality but also informs modern PCB manufacturing workflows, bridging gaps between obsolete techniques and contemporary design constraints.

Transitioning between case studies, you’ll find recurring themes: the role of manual verification in pre-CAD eras, and how component obsolescence drives up PCB manufacturing cost in restoration projects. By studying these systems, you gain insights into the trade-offs that defined 1980s electronics—lessons still relevant when auditing legacy hardware for reuse or documentation.

Conclusion

When studying vintage PCB manufacturing practices through the lens of Microtek’s 1980s designs, you begin to recognize the delicate balance between historical preservation and modern engineering demands. Reverse engineering these systems isn’t just about decoding component-level functionality—it’s a gateway to understanding how PCB manufacturing companies of the past optimized limited resources to achieve reliability in embedded systems. While today’s automated processes prioritize scalability and PCB manufacturing cost efficiency, analyzing these older boards reveals ingenious workarounds for thermal management, signal integrity, and space constraints that still inform niche applications.

The challenges of preserving legacy hardware underscore why PCB manufacturing business models today emphasize documentation and adaptability. Modern tools like X-ray tomography and signal analyzers simplify tasks that once required manual trace mapping, but they can’t fully replicate the contextual knowledge embedded in analog designs. This disconnect highlights a critical lesson: technical progress shouldn’t erase the iterative problem-solving that defined earlier eras. By comparing Microtek’s hand-routed layouts with contemporary high-density interconnect (HDI) boards, you gain perspective on how material innovations and simulation software have reshaped design priorities—yet core principles of robustness and modularity remain timeless.

Ultimately, reverse engineering isn’t just an academic exercise. It bridges the gap between heritage technologies and modern PCB manufacturing workflows, offering actionable insights for restoring legacy systems or designing hybrid solutions. Whether you’re troubleshooting a decades-old control board or optimizing a new prototype, understanding these evolutionary shifts ensures your approach respects both history and innovation.

FAQs

How does reverse engineering vintage Microtek PCBs benefit modern PCB manufacturing practices?

By studying 1980s-era circuit architectures, you gain insights into foundational design principles that inform modern PCB manufacturing companies. Techniques like trace mapping and component-level analysis reveal how constraints of the time influenced decisions, helping engineers optimize PCB manufacturing cost in contemporary projects.

What tools are critical for analyzing legacy Microtek embedded systems?

Multilayer board X-rays, signal analyzers, and thermal imaging help decode obsolete layouts. While these tools differ from those used in today’s PCB manufacturing business, they enable accurate replication of analog subsystems and power management circuits.

Why is preserving 1980s Microtek PCB functionality challenging?

Discontinued components and degraded materials complicate repairs. Modern PCB manufacturing workflows lack compatibility with through-hole designs and manual soldering techniques common in that era, requiring custom solutions to maintain authenticity.

How do PCB manufacturing costs compare between vintage and modern designs?

Retrofitting legacy systems often incurs higher PCB manufacturing cost due to low-volume production and specialized labor. In contrast, automated processes for modern boards reduce expenses, though design complexity in microcontrollers can offset savings.

Can reverse-engineered Microtek PCBs be commercially reproduced?

Yes, but partnering with PCB manufacturing companies experienced in hybrid designs ensures compliance with current safety standards. Documentation of original circuit logic and material specifications is essential for viable reproduction.

Need Professional Support for Your PCB Project?

For tailored solutions bridging vintage and modern PCB manufacturing needs, please click here to consult specialists in legacy system analysis and cost-effective production.