Essential Laws of EMC: Understanding the Fundamental Principles

Introduction to Electromagnetic Compatibility

Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC) represents a critical field in electrical engineering that ensures electronic devices and systems can operate as intended in their shared electromagnetic environment without causing or experiencing unacceptable interference. As our world becomes increasingly saturated with electronic devices—from smartphones to industrial control systems—the importance of EMC has grown exponentially.

The foundation of EMC rests on several fundamental laws and principles that govern how electromagnetic energy behaves, interacts, and propagates. These laws not only help engineers design compliant systems but also provide the theoretical framework for troubleshooting EMC issues when they arise. Understanding these essential EMC laws is crucial for anyone involved in electronic design, from PCB layout engineers to system architects.

This article explores the most important laws that form the bedrock of EMC theory and practice. We will examine seven fundamental principles that every EMC professional should know, explaining their significance and practical applications in real-world engineering scenarios.

Faraday’s Law of Induction

One of the cornerstone principles of EMC is Faraday’s Law of Induction, which establishes the relationship between changing magnetic fields and induced electromotive force (EMF). Mathematically expressed as:

ε = -dΦB/dt

Where ε is the induced EMF and ΦB represents the magnetic flux through a circuit. The negative sign indicates the direction of the induced EMF (Lenz’s Law).

In practical EMC terms, Faraday’s Law explains:

- How changing magnetic fields can induce unwanted voltages in nearby circuits (crosstalk)

- The working principle of inductive coupling between conductors

- The fundamental mechanism behind many electromagnetic interference (EMI) problems

For EMC engineers, Faraday’s Law underscores the importance of:

- Proper cable routing to minimize loop areas that can capture magnetic flux

- Careful design of return paths in PCB layouts

- The use of twisted pair wiring to cancel induced voltages

- Shielding strategies to contain magnetic fields

A classic EMC example is the interference caused when placing sensitive audio cables near power lines—the alternating current in the power line creates a changing magnetic field that induces noise voltages in the audio cables according to Faraday’s Law.

Ampère’s Law and Maxwell’s Addition

While Ampère’s original law related magnetic fields to electric currents, Maxwell’s crucial addition—the displacement current term—completed our understanding of how changing electric fields can also generate magnetic fields. The full Ampère-Maxwell Law is:

∇ × B = μ0J + μ0ε0(∂E/∂t)

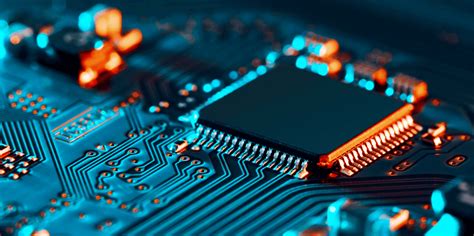

This equation reveals the dual relationship between electric and magnetic fields that forms the basis of electromagnetic wave propagation. For EMC applications, this means:

- Time-varying currents (dI/dt) produce electromagnetic fields that can radiate

- High-frequency signals require special consideration as they efficiently radiate energy

- The law explains how common-mode currents on cables can become effective antennas

In practical design, this principle leads to important EMC practices:

- Minimizing high-frequency current loops

- Using proper filtering to reduce high-frequency content

- Implementing good grounding schemes to control return currents

- Paying special attention to signal edges (rise/fall times) which have high frequency components

The Ampère-Maxwell Law helps engineers understand why seemingly benign circuit traces can become unintentional radiators at high frequencies, potentially causing EMC compliance failures.

Lenz’s Law and Its EMC Implications

Lenz’s Law, often considered a corollary to Faraday’s Law, states that the direction of induced current will always oppose the change in magnetic flux that produced it. This principle has profound implications for EMC:

- Eddy Currents: When a conductor experiences a changing magnetic field, circulating currents (eddy currents) are induced that create opposing magnetic fields. This effect is utilized in:

- Electromagnetic shielding

- Non-contact braking systems

- EMI suppression techniques

- Inductive Component Behavior: Lenz’s Law explains the “choking” action of inductors in EMI filters, where the induced voltage opposes rapid current changes.

- Shielding Effectiveness: Good conductive shields don’t just block fields—they generate opposing fields that cancel incoming interference.

Practical EMC applications of Lenz’s Law include:

- The design of shielded enclosures where induced eddy currents create opposing fields

- Selection of core materials for EMI filters and chokes

- Understanding ground loop interference mechanisms

For example, in a switched-mode power supply, the output inductor works based on Lenz’s Law—when the switch turns off and current tries to decrease rapidly, the inductor generates a voltage that opposes this change, maintaining current flow through the diode.

Coulomb’s Law and Electric Field Coupling

While Faraday’s and Ampère’s Laws deal with magnetic fields and time-varying phenomena, Coulomb’s Law describes the fundamental electrostatic force between charges:

F = k(q1q2)/r²

This inverse-square law governs electric field interactions that are crucial for understanding:

- Capacitive coupling between conductors

- ESD (electrostatic discharge) phenomena

- Electric field shielding requirements

In EMC terms, Coulomb’s Law helps explain:

- How high-impedance circuits are particularly susceptible to electric field interference

- The mechanism behind capacitive crosstalk between adjacent traces or cables

- The importance of maintaining proper spacing between high-voltage and sensitive low-voltage circuits

Practical EMC measures derived from Coulomb’s Law include:

- Using guard rings around sensitive inputs

- Implementing proper trace spacing on PCBs

- Selecting appropriate dielectric materials

- Applying electrostatic shielding when needed

For instance, in a high-impedance sensor circuit, even nearby low-voltage lines can capacitively couple significant noise due to the electric fields described by Coulomb’s Law—a phenomenon that becomes more pronounced at higher frequencies.

The Inverse Distance Law for Field Strength

A crucial practical principle in EMC is the Inverse Distance Law, which states that the strength of electromagnetic fields from a point source decreases with the inverse of the distance (for near fields) or inverse square of the distance (for far fields):

Near field (inductive): H ∝ 1/r

Near field (capacitive): E ∝ 1/r

Far field: E, H ∝ 1/r²

This relationship has several important EMC implications:

- Doubling the distance from a source typically reduces interference by 6dB (near field) or 12dB (far field)

- It explains why keeping susceptible devices away from noise sources is effective

- It helps predict how shielding effectiveness varies with placement

Practical applications include:

- Determining safe separation distances between noise sources and sensitive circuits

- Planning equipment layout in control panels or data centers

- Evaluating shielding requirements based on source-receiver distances

For example, in a factory automation setting, keeping motor drive cables at least 30cm away from sensor wiring can often reduce induced noise by 20dB or more, simply by leveraging the Inverse Distance Law.

Skin Effect and Its Impact on EMC

The skin effect describes how alternating current tends to flow near the surface of a conductor, with the current density decreasing exponentially with depth. The skin depth (δ) is given by:

δ = √(ρ/πfμ)

Where ρ is resistivity, f is frequency, and μ is permeability.

This phenomenon significantly affects EMC in several ways:

- At high frequencies, conductors provide less effective shielding as currents concentrate on the surface

- The resistance of conductors increases with frequency due to reduced effective cross-section

- Different frequency components in a signal may follow different paths

EMC engineering applications of the skin effect include:

- Designing effective shields and enclosures

- Selecting appropriate conductor materials and platings

- Understanding high-frequency grounding behavior

- Designing EMI filters and ferrite beads

For instance, in RF shielding, a thin layer of high-conductivity material (like silver or copper) is often sufficient for high-frequency shielding because of the skin effect, while lower frequencies may require thicker materials or different approaches.

Wave Impedance and Field Characterization

The wave impedance (Zw) of an electromagnetic field, defined as the ratio of electric to magnetic field components (E/H), is a crucial parameter for understanding coupling mechanisms and designing effective countermeasures. The wave impedance varies depending on the field region:

- Near field (reactive region):

- Electric field dominant: Zw > 377Ω

- Magnetic field dominant: Zw < 377Ω

- Far field (radiation region): Zw = 377Ω (free space impedance)

This distinction is vital for EMC because:

- Different shielding techniques are required for high vs. low impedance fields

- Measurement approaches must account for the field region

- Coupling mechanisms differ based on wave impedance

Practical EMC applications include:

- Selecting appropriate shielding materials (conductive vs. permeable)

- Designing effective filters based on coupling mechanisms

- Proper probe selection for EMI troubleshooting

- Antenna design for emissions testing

For example, when dealing with low-impedance magnetic fields near power transformers, mu-metal (high permeability) shields are often more effective than standard conductive shields, while electric field shielding at the same distance might require conductive materials.

Conclusion: Integrating EMC Laws into Practical Design

Understanding these fundamental EMC laws provides engineers with a powerful framework for both designing compliant systems and troubleshooting EMC issues. The seven principles discussed—Faraday’s Law, Ampère-Maxwell Law, Lenz’s Law, Coulomb’s Law, Inverse Distance Law, Skin Effect, and Wave Impedance—form an interconnected web that explains most electromagnetic phenomena encountered in real-world applications.

Successful EMC design requires applying these principles holistically:

- Early consideration of potential coupling mechanisms during schematic design

- Careful physical layout that minimizes loop areas and unwanted coupling

- Appropriate shielding strategies based on frequency and field characteristics

- Proper filtering that accounts for both conducted and radiated paths

- Systematic testing and measurement to verify design choices

As electronic systems continue to increase in complexity and density, these fundamental EMC laws remain constant. By mastering these core principles, engineers can develop intuition for EMC challenges and create robust designs that perform reliably in increasingly crowded electromagnetic environments. The most effective EMC strategies don’t rely on “black magic” or trial-and-error, but on a solid understanding and application of these fundamental physical laws that govern all electromagnetic phenomena.